Guillain-Barré Syndrome

DEFINITION

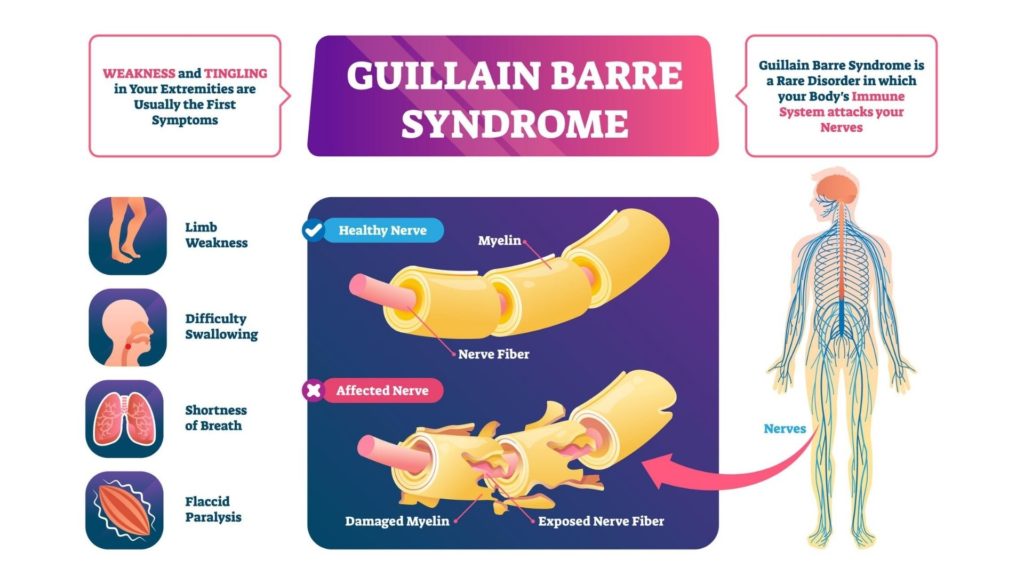

Guillain-Barré syndrome is a rapid-onset autoimmune disorder of the peripheral nervous system, in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own nerves.

It is named after the two French neurologists who first described it in 1916.

DESCRIPTION

Guillain-Barré syndrome is a rare but serious condition marked by progressive symptoms affecting the nerves and, later, muscles.

Its typical pathology begins two to four weeks after the patient has contracted a relatively minor viral or bacterial infection.

In most instances, the first symptoms include localized nerve pain, tingling sensations, and numbness, which then spreads throughout the body, leading to muscle weakness and, in severe cases, partial or total paralysis.

Extreme symptoms are considered a medical emergency, and the majority of patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome require hospitalization.

DEMOGRAPHICS

Guillain-Barré syndrome occurs worldwide and has a worldwide incidence rate of 1.5–3 cases per 100,000 people.

In the U.S., the incidence rate is similar, with several studies estimating that the annual incidence rate is 1.2–3 per 100,000 people.

While researchers have noted that older people seem to be at increased risk of developing Guillain-Barré syndrome, the condition also affects children and adolescents, especially those over the age of 15.

It is sporadic in newborn babies and infants.

CAUSES AND SYMPTOMS

While the exact cause of Guillain-Barré syndrome has yet to be definitively identified, approximately 60% of cases occur after the patient has contracted a viral or bacterial infection.

The preceding infection is frequently minor in nature and can include conditions like the common cold, strep throat, Zika virus infection, or an infection of the stomach or bowels.

Latent cytomegalovirus infections have also been linked with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Researchers believe that the presence of these pathogens may alter the normal characteristics of nerve cells, causing the body’s immune system to mistake them for intruders and attack them.

The initial symptoms of Guillain-Barré syndrome include tingling sensations and localized weakness, usually beginning in the feet or legs before spreading upward to the arms and torso.

Patients frequently describe these symptoms as “feeling like pins and needles.”

However, in about 10% of cases, patients report the initial symptoms of tingling and weakness in the eyes, face, or arms before the symptoms spread to other regions of the body.

As the condition progresses, patients experience intensifying prickling sensations and weakness that begin to affect muscle groups, leading to problems with balance and coordination and possible impediments to chewing, speaking, swallowing, eye movements, and facial movements.

Blood pressure may rise or fall, and the patient’s heart rate may become elevated. Some patients also report breathing difficulties, loss of bladder control, disrupted bowel function, and severe aches or cramps that worsen at night, often leading to sleep loss.

In extreme cases, patients go on to develop partial or complete paralysis.

Symptoms usually peak two to four weeks after their initial onset, then reach a plateau phase before beginning to diminish.

The plateau phase normally lasts approximately two to four weeks. However, some patients experience lingering effects for months or even years after first developing the syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

Because the early symptoms of Guillain-Barré syndrome are similar to those seen in numerous other neurological disorders, diagnosing the condition can be difficult in its initial stages.

If the patient’s doctor suspects Guillain-Barré syndrome, he or she will usually begin with a physical examination and questions about the patient’s medical history before recommending diagnostic tests.

These tests may include the following:

- Electromyography: This procedure involves the insertion of thin, needle-like electrodes into the muscle groups most severely affected by the patient’s symptoms. The electrodes then record the activity level of nerves in the muscles under examination.

- Lumbar puncture: Informally known as a spinal tap, a lumbar puncture is used to collect fluid from the patient’s spinal canal. This fluid is then tested for deviations that are frequently seen in Guillain-Barré patients.

- Nerve conduction analysis: In this test, electrodes are affixed to the patient’s skin and are used to deliver a mild electric current that tests the reactions of the underlying nerves.

TREATMENT

While symptoms usually diminish with time, there is no cure for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Treatment approaches focus on hastening the patient’s recovery and minimizing discomfort.

Two primary treatments are used to inhibit the syndrome’s progression and support a faster recovery: plasma exchange and immunoglobulin therapy.

Plasma exchange, which is also known as plasmapheresis, involves removing the liquid component of the patient’s blood, known as plasma.

The plasma is then separated from the leftover blood cells, and the blood cells are returned to the patient’s body, triggering the production of new plasma.

The new plasma will not contain the immune system antibodies causing the misdirected attacks on the patient’s nerves, thus reducing symptoms and supporting recovery.

Immunoglobulin therapy also aims to inhibit the damaging activity of the patient’s immune system, using blood given by donors to reduce harmful antibody concentration in the bloodstream and increase healthy antibodies.

Prescription medications may also be administered to help relieve the patient’s symptoms and prevent complications.

Analgesics are used to relieve pain, and blood-thinning drugs can be given to prevent potentially dangerous blood clots, which can arise during extended periods of paralysis or immobility.

Physical therapy and exercise therapy might also be recommended during the recovery period to help the patient regain lost strength and muscle tone.

PROGNOSIS

Adult Guillain-Barré syndrome recovery rates are as follows:

- approximately 80% of patients can walk unassisted within six months

- approximately 60% of patients regain their motor strength and control within one year

- approximately 5–10% of patients suffer delayed recovery or permanent disability

Children and adolescents tend to make faster and more complete recoveries from Guillain-Barré syndrome than adults.

PREVENTION

Because there is a strong link between Guillain–Barré syndrome and viral and bacterial infections, the condition may be preventable by minimizing exposure to pathogens.

Limiting close personal contact with people suffering from viral or bacterial infections and practicing proper handwashing hygiene might help reduce the risk of contracting the disease.

PARENTAL CONCERNS

Children who have recently contracted bacterial or viral infections should be monitored in the weeks following their recovery for possible symptoms of Guillain–Barré syndrome.

It is important to note that the preceding viral or bacterial infection need not be serious in nature for Guillain–Barré syndrome to arise. While the underlying infection may be contagious,

Guillain–Barré syndrome itself cannot be transmitted from one person to another.

KEY TERMS

- Antibody— An agent of the immune system that seeks, identifies, and attacks pathogens and harmful microbes.

- Autoimmune disorder— A type of disease affecting the body’s immune system, in which the immune system mistakes healthy tissues for intruders and attacks them with the intent of destroying them.

- Cytomegalovirus— A type of herpes virus that is linked to the salivary glands. It usually does not produce symptoms, except in newborn babies and patients with compromised immune systems.

- Latent infection— A type of viral infection in which the virus is present in the body but does not produce symptoms until a much later time, if at all—pathogens— Infectious agents, including viruses, fungi, parasites, and bacteria. The term encompasses any foreign body that is capable of causing disease.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR DOCTOR

- If the patient previously contracted a viral or bacterial infection, is the original infection still active? And does it pose any risk of later complications?

- Are the patient’s symptoms expected to progress, or have they been effectively neutralized?

- What lingering or long-term effects or complications might occur in the weeks and months ahead?

- How long is the patient’s recovery period expected to last?

- How severe is this case?

- What are the risks involved with the tests and procedures used to diagnose Guillain–Barré syndrome?

Resources

BOOKS

Ka, Shari. Guillain–Barré Syndrome: My Journey Back. Bloomington, IN: Trafford Publishing, 2011.

Steinberg, Joel S., and Gareth John Parry. Guillain–Barré Syndrome: From Diagnosis to Recovery. St. Paul, MN: AAN Enterprises, 2010.

PERIODICALS

Roodbol, J., et al. “Recognizing Guillain–Barré Syndrome in Preschool Children.” Neurology 76, no. 9 (March 2011): 807–810.

Sander, Howard, et al. “Trends in Outcome and Hospitalization Charges of Pediatric Patients Admitted with Guillain Barré Syndrome in the United States.” Neurology 80, no. 1 (February 2013): 1–136.

Willison, Hugh J., Bart C. Jacobs, and Pieter A. van Doorn. “Guillain–Barré syndrome.” The Lancet 388, no. 10045 (2016): 717–727.

WEBSITES

Mayo Clinic staff. “Guillain–Barré Syndrome.” Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/Guillain-Barrésyndrome/basics/definition/con-20025832 (accessed April 8, 2020).

NINDS. “Guillain–Barré Syndrome Fact Sheet.” National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U.S. National Institutes of Health. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/gbs/detail_gbs.htm (accessed April 8, 2020).

ORGANIZATIONS

National Organization for Rare Disorders, 55 Kenosia Ave, Danbury, CT, United States 06810, (203) 744-0100, Fax: (203) 798-2291, http://www.rarediseases.org.